The Durability Cliff: Why MLB Needs 42.7% More Pitchers

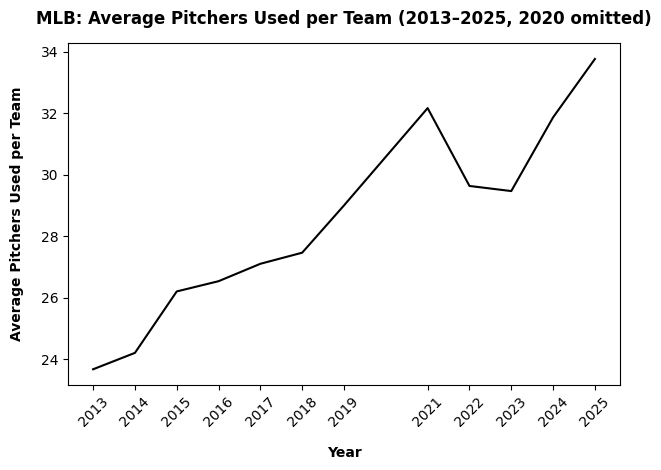

Since 2013, Major League Baseball teams have needed 42.7% more pitchers to cover the same seasonal innings workload.

That is not a philosophical shift. It is a structural one.

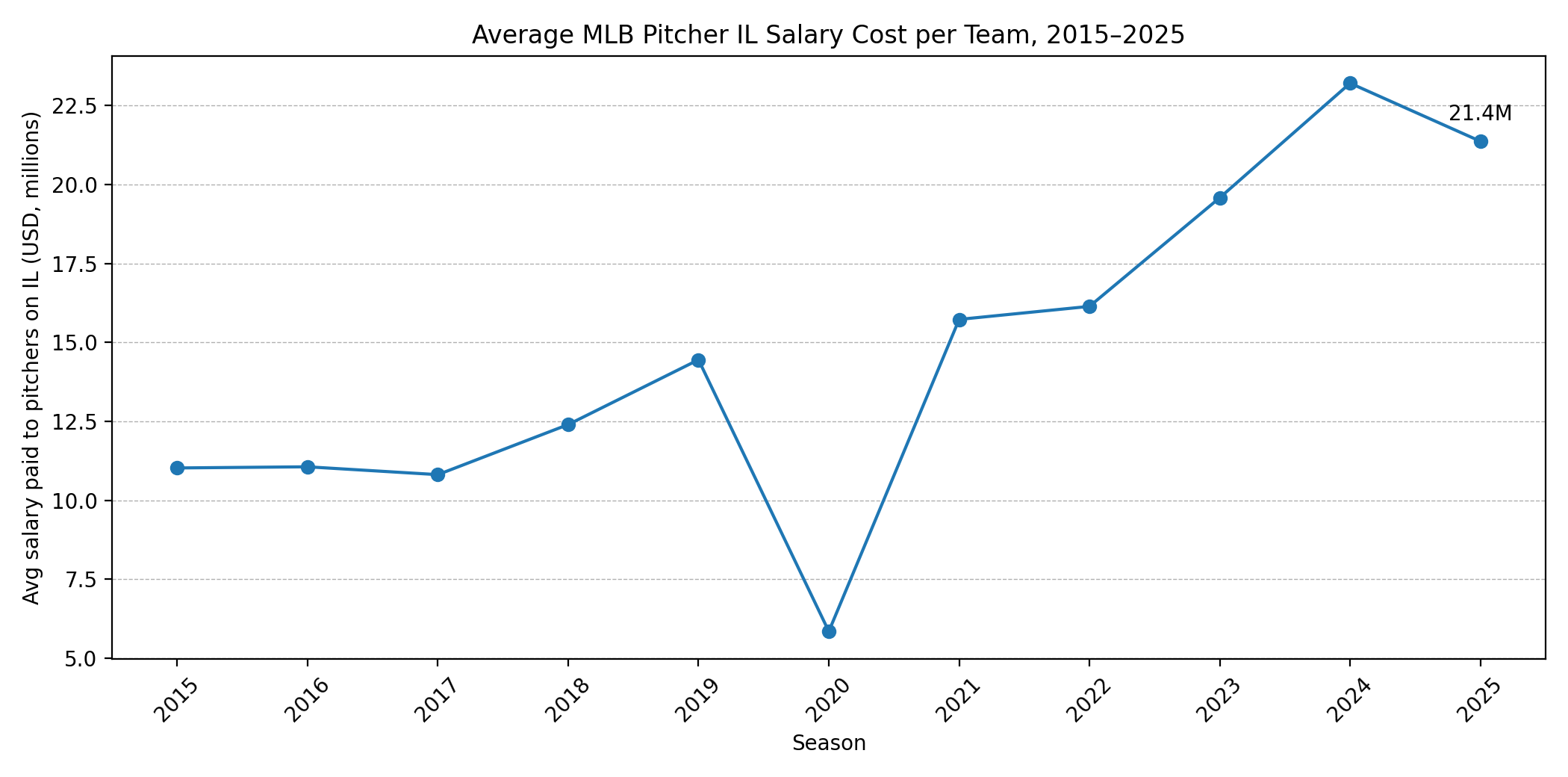

Organizations aren’t choosing volume because it’s optimal. They’re relying on volume because the sport’s durability floor has collapsed. As the number of arms required to survive a season has climbed, the consequences have followed: Days Lost to the Injured List are up 71%, and in 2025 clubs paid an estimated $641 million in salary to pitchers who were physically unable to take the mound.

Baseball has always lived with injuries. What’s different now is how central the injury cycle has become to roster construction—and how much it has reshaped the pathway to the big leagues.

Opportunity Created by Breakdown

The increase in pitching injuries has opened doors for more minor league pitchers to reach the majors. The demand for innings is constant, and the supply of healthy, reliable arms is not. When the durability floor sinks, opportunity rises—not because the system is more generous, but because it is more desperate.

That desperation carries an unintended consequence: it reinforces the behaviors that helped create the problem.

Players are incentivized to pursue the same performance training measures that rooted the injury cycle in the first place, then continue doubling down on those behaviors because they still generate opportunity. The system keeps rewarding what it is trying to survive.

It’s a difficult loop to break because it isn’t driven by ignorance. It’s driven by incentives.

Why “Solutions” Don’t Stick

This is why so many injury-prevention solutions—research, technology, protocols, tools—struggle to scale beyond small pockets of progress.

If you cannot change how a pitcher is rewarded, you cannot change the behavior that pitchers choose to repeat.

Private facilities and training organizations can sell performance and “stuff.” If that product continues to produce scholarships, draft status, promotions, and chances, there is no obvious reason for those businesses to deviate from the model. And there is little external pressure to change it, because the financial burden of injuries sits primarily with MLB organizations—the very entities that are paying to cover the damage.

The incentives are misaligned, and the results reveal the cost.

The Cost of Chasing “Stuff”

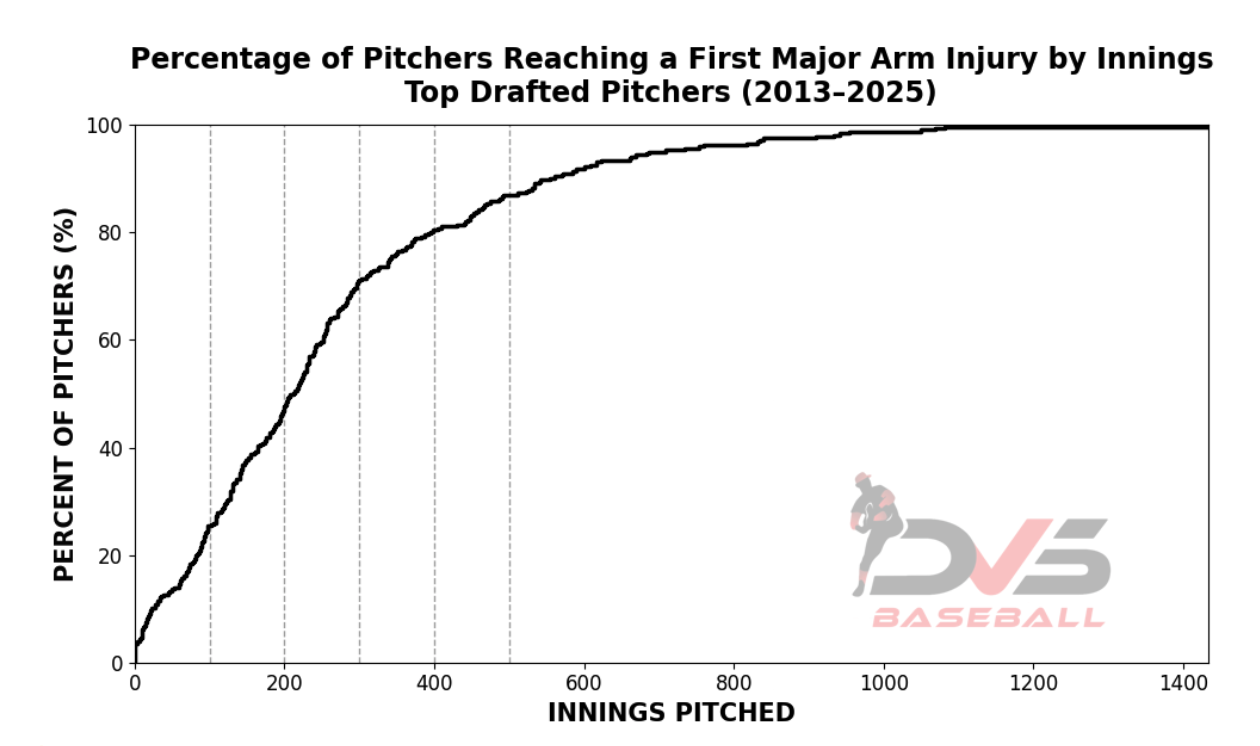

Despite $1.27 billion spent in signing bonuses for top-tier “stuff,” 74.3% of those pitchers produced zero MLB innings for the team that drafted them.

That number does not indict scouting alone. It indicts outcomes.

Teams are investing heavily in traits that generate opportunity—velocity, shape, strikeout ceilings—while the sport simultaneously struggles to develop and retain the one resource a season demands: reliable innings.

By 2026, the logic is hard to argue with. If the pipeline produces enough replacement arms to cover the losses, the system can continue—even if it is inefficient, even if it is expensive, even if it burns through careers.

The Durability Cliff

The “Durability Cliff” is now steep enough that pitchers drafted after 2019 are failing at nearly twice the rate of previous generations—hitting a wall at just 180 innings.

That is the hidden crisis inside the modern pitcher economy. Baseball has not simply lost workhorses. It has normalized a developmental path that rarely produces them.

The sport is left with more arms, fewer innings per arm, and a constant search for the next replacement—an ecosystem that can look productive on the surface because opportunity is abundant, even while the foundation deteriorates.

What Still Matters

And yet, the sport’s oldest truth hasn’t changed: pitchers still need to pitch and get outs to stay employed.

There are plenty of scouts, front office executives, agents, and fans who don’t care how hard a pitcher throws if he can help a team win. If he can do it longer—if he can be available, repeat performance, and stabilize a staff—that isn’t a bonus. It is value.

The problem is that value is not always what the system rewards early enough, or often enough, to shape development at scale.

The Unpopular Work

Developing traditional starting pitchers isn’t popular. It is slower. It is harder to sell in a highlights culture. And it requires a combination that cannot be manufactured by technology alone: sequencing, physics, energy, function—paired with pitchability and execution.

That last piece is the hardest. It takes wisdom. It takes experience. It takes people who have lived the work, and can teach what happens between the metrics.

But it can be done.

Avoiding the cliff is not about rejecting modern performance. It’s about building pitchers who can carry it—without breaking.

That is the work we’re committed to at DVS Baseball: helping pitchers prove they can pitch, then rewarding them for consistency, availability, and the ability to take the mound again and again.

Because the sport doesn’t need more replacement pitchers.

It needs more pitchers who can actually hold the innings.