The Extinction of the Workhorse: A Data-Driven Look at the Decline of Starting Pitching

The baseball world is currently fixated on a paradox: the athletes are throwing harder than ever before, yet the "Starting Pitcher" is becoming a vanishing breed. What was once the cornerstone of the game—the 200-inning workhorse—has been replaced by a revolving door of high-velocity arms and frequent trips to the 60-day Injured List.

At DVS Baseball, we believe that if you want to fix a problem, you first have to define its scope. We recently completed an exhaustive case study to determine why the industry is failing its most talented arms. The results suggest that the decline of the starting pitcher isn't a fluke of nature—it’s a result of modern design.

The Operating Table: A Personal Catalyst

My obsession with pitcher durability isn't just academic; it’s personal. In 2004, I was living the dream, drafted 33rd overall by the Los Angeles Dodgers. I had the velocity and the pedigree, but two years later, I found myself waking up from anesthesia. I had lost 80% of my bicep tendon.

I’ll never forget what the surgeon told me as I recovered:

"I don’t know if you have 6,600, 600, or 6 innings left. But I do know that the way you throw the baseball led to this type of injury."

That moment changed my career and eventually birthed the DVS scoring system. It forced me to realize that as a pitcher, your "clock" is ticking from the moment you start throwing. The question for every player, parent, and coach is: How fast are you letting that clock run down?

The 1,100 Pitcher Study: Defining the "Cliff"

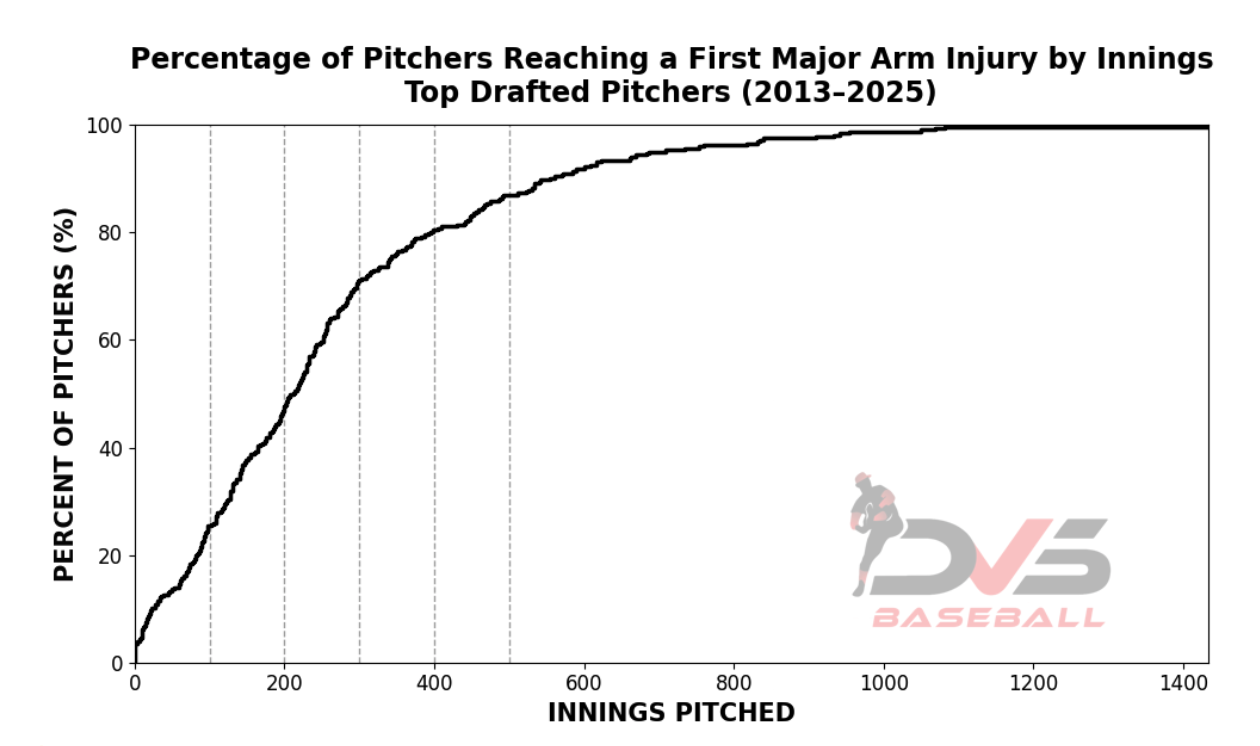

To understand the current state of the game, we tracked the top three pitchers drafted and signed by every MLB organization each year since 2013. This provided a sample size of over 1,100 of the most elite arms in the world.

The data revealed a landscape of attrition:

The Injury Rate: 38% of these elite pitchers suffered a documented arm injury.

The Severity: 28% suffered a "Major" injury, defined as missing 90 or more days of play.

The 1,000-Inning Club: Out of 1,100+ pitchers, only three reached the 1,000-inning milestone.

One of those three is Aaron Nola. To put his durability in perspective, Nola has thrown more professional innings than 20 entire MLB organizations’ top picks combined. He isn't just an outlier; he is a different species in the modern era.

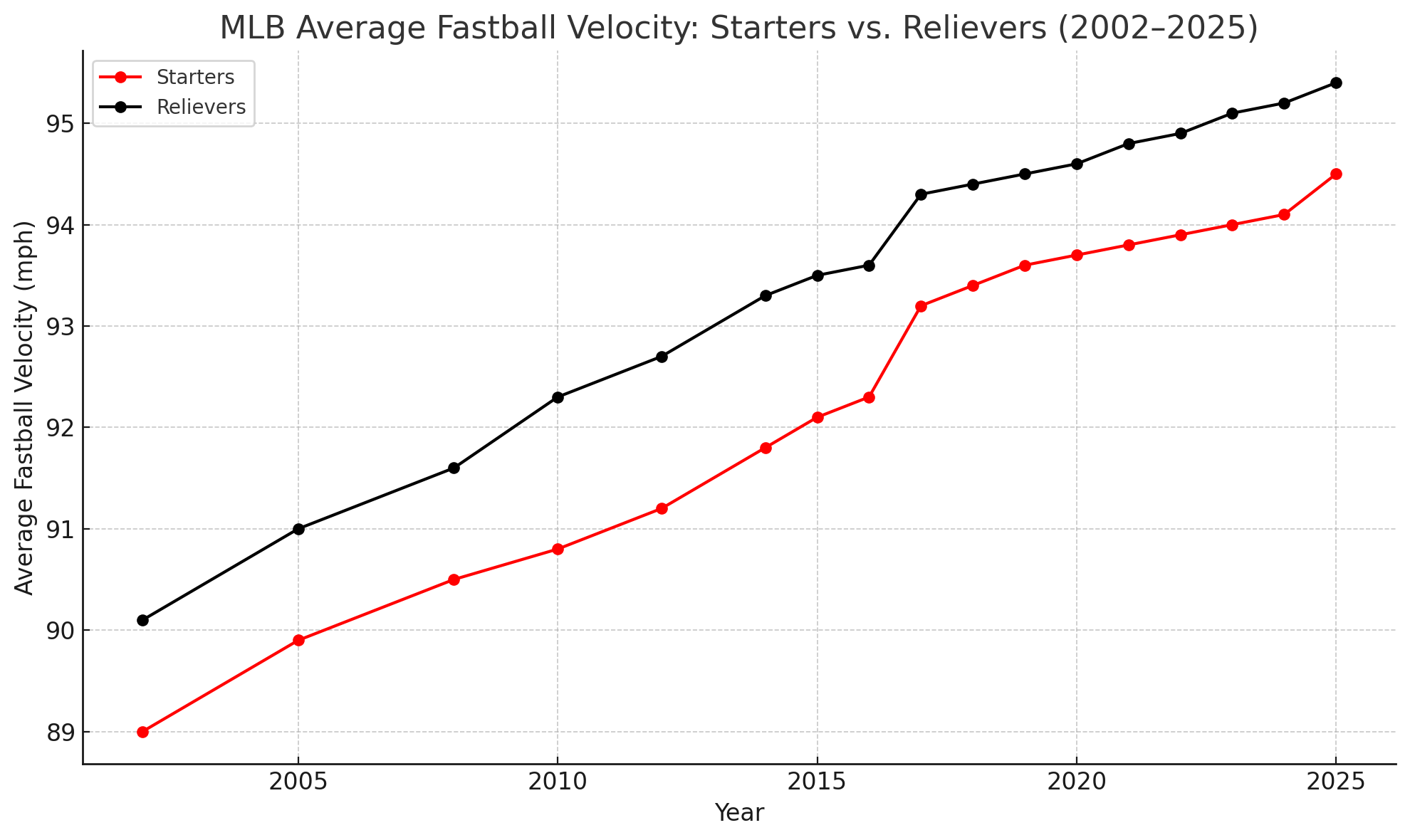

The Velocity Trap and the Inning Threshold

Since 2000, velocity has been the primary currency of the MLB Draft. While the increase in "velo" is a testament to better training and athleticism, it has come at a steep cost. The industry has mastered how to create energy, but it has failed to teach pitchers how to manage it.

Our research found a distinct "Inning Threshold" where the body typically breaks under the current professional development model:

College Draftees: Average roughly 307 innings (including their college career) before a major injury occurs.

High School Draftees: Reach the injury cliff at just 160 innings.

Because 75% of drafted players now come from the college ranks, organizations are often drafting players who are already nearing their "injury threshold." They hope to squeeze out a two-to-three-year window of high performance before the inevitable breakdown occurs. This is "disposable" pitching by design.

Engineering Availability: The DVS Path Forward

The tragedy of these statistics is that many of these injuries are preventable. The human body hasn't suddenly become less capable of throwing 200 innings; rather, the leadership, strategy, and mechanical priorities of the game have shifted away from durability.

At DVS Baseball, we focus on the Foundation of Movement. It’s not about "throwing soft" to stay healthy; it’s about understanding the biomechanics of how energy is produced, transferred, and—most importantly—absorbed by the body.

If you are a pitcher in today's landscape, you cannot afford to be naive. You cannot assume the "system" is designed to keep you on the mound for a 15-year career. You have to take an active role in engineering your own durability. You have to ask the hard questions about your delivery and your workload before your clock hits zero.

Availability is the greatest ability a pitcher can have. It’s time we started training like it.